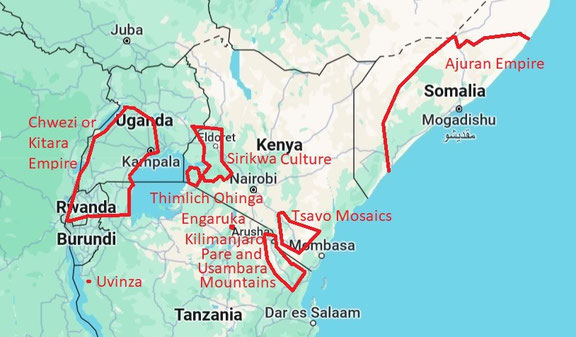

East African Interior at the End of the 15th century.

------------------------------------------------------

All the different cultures mentioned are those who left enough very visible archaeological remains so that research on them happened early on. For all other places in East Africa we have to wait till archaeology has bigger budgets.

Ajuran Empire

----------------

Archaeology in the interior of Somalia has not progressed enough to show the trade with the coast. As well as list the ruins of the Ajuran archaeological remains. So only oral history sources can be used here.

Find them on my webpages:

-Merca

- Medieval Mogadishu by Sharif Aydurus.

Sirikwa culture

---------------

Taken from: Wikipedia Sirikwa culture.

The Sirikwa culture was the predominant Kenyan hinterland culture. The archaeological evidence indicates that from about AD 1200, the Central Rift and Western Highlands of Kenya were relatively densely inhabited by a group (or groups) of people who practiced both cereal cultivation and pastoralism (and crafts). (With traces of a Proto-Sirikwa culture dating from c. 700 AD to c. 1200 AD). They made occasional use of metals and created distinctive roulette-decorated pottery. These people are principally known from their characteristic settlement sites, commonly known as 'Sirikwa holes or hollows'. These comprise a shallow depression, sometimes reinforced at the edges by stone revetments, around which habitation structures were built. There are a number of indicators that the central depression was a semi-fortified cattle boma (=corral), with people living in connected huts around the exterior. This way of life would decline and eventually disappear by the 18th and 19th centuries.

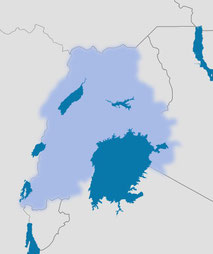

Sirikwa-inhabited territory is believed to have extended from Lake Turkana in the northern part of the Great Lakes region to Lake Eyasi in the south. Its cross-section stretched from the eastern escarpment of the Great Rift Valley to the foot of Mount Elgon. Some of the localities include Cherengany, Kapcherop, Sabwani, Sirende, Wehoya, Moi's Bridge, Hyrax Hill, Lanet, Deloraine (Rongai), Tambach, Moiben, Soy, Turbo, Ainabkoi, Timboroa, Kabyoyon, Namgoi and Chemangel (Sotik).

Archaeology:

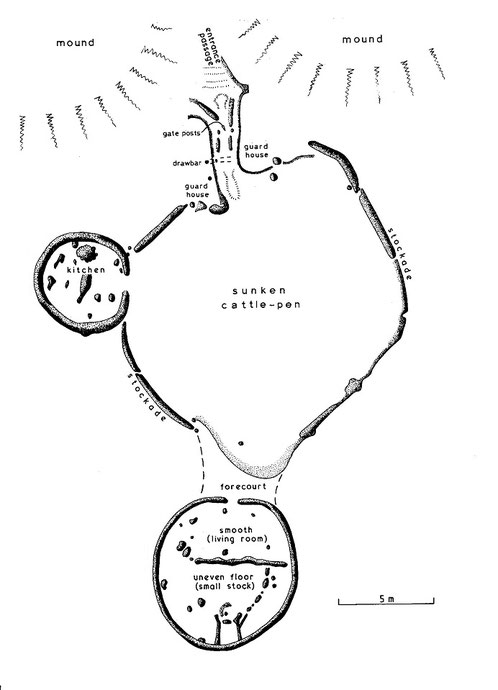

Numerous saucer-shaped hollows have been found in various areas on the hillsides of the western highlands of Kenya and in the elevated stretch of the central Rift Valley around Nakuru. These hollows, having a diameter of 10–20 metres and an average depth of 2.4 metres, are usually found in groups sometimes numbering less than ten and at times more than a hundred. Excavations at several examples of these sites in the western highlands and in the Nakuru area have shown that they were deliberately constructed to house livestock.

These hollows were surrounded by a fence or stockade and on the downhill side, a single gate, usually with extra works and flanking guard houses. In rocky terrain, notably the Uasin Gishu Plateau and the Elgeyo border, stone walling substituted for fencing or provided a base for the same. At the time of the first recorded accounts during the late 18th centuries, some of the dry-stone walling could still be seen though they were mostly in deteriorated state.

From the remains it is apparent that houses were not built inside the actual Sirikwa holes but were attached however and were constructed on the outer side of the fence, being approached through the stock-pen and entered through a connecting door. These hollows are mostly covered over by grass and bush today.

The Sirikwa practiced pastoralism (but were not nomadic as they send the young man out for seasonal grazing). They herded goats, sheep, and cattle. There is also evidence that they raised donkeys, as well as domesticated dogs. The Sirikwa focused on milk production, which is shown by the lack of lactating age cows in archaeological assemblages. Large herds of sheep and goats were kept for meat, and made up a large proportion of the Sirikwa diet.

A large Sirikwa hole at Chemagel (Sotik) near the southern end of the zone. It is only 200 years old. Every day mud and dung were removed and with domestic waste added to the mounds flanking a curving hollow passage (=the mounds hide the gate from view). And the 2.4m deep cattle pen is also out of view. As can be seen the place is guarded against small bands of attackers. But with new military organization into bigger groups this type of living needed to be abandoned.

Thimlich Ohinga

-----------------

Taken from: Thimlich Ohinga; Wikipedia

Thimlich Ohinga is a complex of stone-built ruins in Migori county, Nyanza Kenya, in East Africa. It is the largest one of 138 sites containing 521 stone structures that were built around the Lake Victoria region in Kenya. These sites are highly clustered. The main enclosure of Thimlich Ohinga has walls that are 1–3 m in thickness, and 1–4.2 m in height. The structures were built from undressed blocks, rocks, and stones set in place without mortar. The densely packed stones interlock. The site is believed to date to the 15th century or earlier.

The scale of Thimlich Ohinga and related structures points to an organised community that could mobilise labour and resources. The readily available rocks from the local environment provided the materials with which the enclosures were constructed. Luo oral traditions state that the enclosures were built for protection against wild animals, cattle rustlers and other hostile groups. These traditions suggest that Thimlich Ohinga was constructed by the then-inhabitants to serve as protection against outsiders. Aside from being a defensive fort, Thimlich Ohinga was also an economic, religious, and social hub.

Builders and inhabitants.

Accurate dating of the site remains inconclusive. Quatz flakes of the late stone age type have been found on the site and presumed to predate it. Archaeological and historical studies have concluded that the original builders and later inhabitants maintained a pastoral tradition where cattle played a key role in the economy. These studies also conclude that socio-political organisation also played a crucial role in the establishment of Thimlich Ohinga and other surrounding fortified structures.

Archaeological and ethnographic analysis of the sites has shown that the spatial organisation most closely resembles the layout of traditional Luo homesteads. For example, Luo homesteads are circular with a focal meeting point adjacent to a central livestock enclosure, a pattern observable in Thimlich Ohinga. Pottery recovered on the sites also demonstrate specific decorative patterns commonly found among Western Nilotic speakers (Luo) and not among Bantu speakers. These findings suggest that the inhabitants of these structures also contributed to the ancestry of present-day inhabitants of the area who identify as members of the Luo community. For reasons yet unknown, Thimlich Ohinga was abandoned by the original builders. Over time, other communities moved into the area in the period between the 15th and the 19th centuries and those who lived within the complexes maintained them by repairing and modifying the structures. The re-occupation and repair did not interfere with the preservation of the structures. The site was vacated for the last time during the first half of the twentieth century as the colonial administration established peace and order in the region. The families living in the enclosures moved out into individual homesteads using euphorbia instead of stone as fencing material. A shift in mindset occurred as the local community moved from a communal living set-up to a more individualistic one.

Architectural style

Thimlich Ohinga was constructed using unshaped and random loose stones made from local basalt. Mortar and dressing were not used and therefore great care and skill was needed to ensure stability. The walls at Thimlich Ohinga are free standing, 1 m thick with no dug foundation. They are 0.5–4.5 m in height. The ovoid walls intersect with each other in a curved and zigzag fashion, using intermittent buttresses to add to stability. Similar enclosures found in Northern Nyanza have other features such as rock pillars and stone linings. The gates have stone lintels and engraved markings.

Thimlich Ohinga is an example of defensive savanna architecture, which eventually became a traditional style in various parts of East and Southern Africa. Taken together with the other stone built enclosures, Thimlich Ohinga creates the impression of a society with a centralised system of control and communal lifestyle that was spread around the Lake Victoria region. Later forms of this stone-walled architecture can be seen on some traditional houses in Western and South-Western Kenya.

Internal features

A watchtower constructed from raised rocks is found immediately after the entrance. There are three entrances to the main monument at Thimlich Ohinga with one west facing and two east facing. The structures are partitioned into corridors, several smaller enclosures and depressions. Circular depressions and raised platforms are found where the houses within the enclosures were constructed. The main monument has six house pits and five enclosures within it. Grinding stones for grain are also found at the site. Livestock pens for cattle, sheep, goats, chicken, guinea fowl with retaining walls for gardens were also built. Animal remains on the site include domestic and wild species such as cattle, ovicaprids (sheep and goats), chicken, fish, hartebeest (Kongoni), duiker and hare. The entryways were intentionally constructed as small passageways, so that potential intruders could be quickly subdued by guards stationed on the watchtower near the entrance. The watchtower gives a good view of the whole complex and surrounding area. The enclosures also feature smaller side forts which contained houses, dining areas, animal pens, and granaries. An iron smith was present at Thimlich Ohinga. Iron slag, smoking bellows and iron objects have been found in a partially walled area next to the main enclosure. Imported glass beads at the site indicate that Thimlich Ohinga was part of a network of long-distance trade.

Taken from: Thimlich Ohingini by Dr Simiyu Wandibba 1986.

He carried out some preliminary excavation in the main enclosure. Inside there are five smaller enclosures which were probably used as cattle kraals, or pens, for smaller stock. At least six house pits were identified. Test pits were sunk in four selected areas. One of them was a house pit which yielded pottery, stone artefacts, beads and bones. The stone artefacts consist of grindstone and quartz flakes of the late Stone Age, presumably much older than the monument. Most of the pottery was decorated with a knotted cord-roulette, the motifs being similar to those on modern Luo pottery in the locality. The beads were of different colours and sizes. Some are made of Gusii soapstone, whilst others are of imported glass. The presence of the beads on the site indicates some form of exchange between the inhabitants of the site and the outside world.

Taken from: Drivers and trajectories of land cover change in East Africa: Human and environmental interactions from 6000 years ago to present by Rob Marchant and all.

Some of the many enclosures have drystone walls and drove-ways arranged in a spoke-like fashion around the main enclosure, creating a series of radiating agricultural plots. Stone terracing is also evident at some sites. Nearest Neighbour and Cluster Analyses of their distribution and topographic setting, indicate a preference for hill-top and upper slope locations close (typically ≤3 km) to a permanent water source (Onjala, 2003). They also tend to occur in distinct clusters, with the highest density around the site of Thimlich Ohinga, and elsewhere in Macalder district, Migori County. Thimlich Ohinga is the largest and best-preserved example. Faunal remains from this site attest to the herding of cattle and small stock, with fish and wild game supplementing local diets. Grain-bin foundations, and upper and lower grinding stones indicate the importance of crop cultivation.

Chwezi or Kitara Empire.

--------------------------

The three archaeological sites of Ntusi, Munsa, Kibiro where glass beads and cowrie shells were found were important places in this empire. (See my webpage: Uganda: Ntusi, Munsa, Kibiro.)

The Chwezi or Kitara empire (W and N of lake Victoria) according to J.W. Nyakatura.

Taken from: The Collapse of the Chwezi Empire by Enid Karen Nabumati

The Chwezi dynasty is thought to have been related to the presiding Tembuzi dynasty in a way that King Isaza, the last ruler of the latter, before descending to the underworld, fathered a child (Isimbwa) with Nyamate, the daughter of the underground king Nyamionga.

Isimbwa then fathered Ndahura, the first king (Mukhwezi) of the Kitara Empire.

Just like their predecessors the Tembuzi, the Chwezi possessed divine powers and at the same time, human characteristics and were thus referred to as demi gods since they belonged to earth and the underworld as well. It was their divine nature which made them great magicians and hunters.

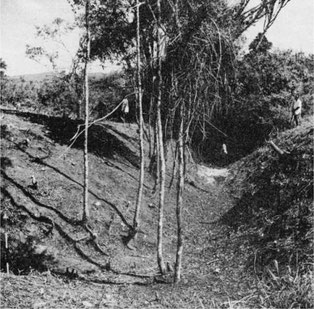

Taken from: East Africa Through a Thousand Years by Gideon S. Were, Derek Wilson · 1987

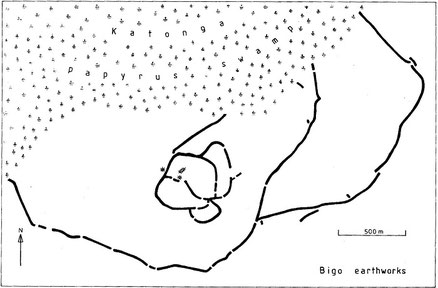

The rise of the Chwezi could be accounted for either by a struggle within the ruling pastoral families which ended with a new ruling group taking over, or perhaps a new group of immigrants from the north took control of the Tembuzi kingdom. The Chwezi or Hima are said to have introduced a superior material culture. It included barkcloth manufacture, coffee growing, earthwork fortifications and reed palaces. Their pottery consisted of round bowls, jars, shallow basins and decorated dishes with feet. — The coming of the Chwezi caused important social and political changes which affected the history of the region. Before the Chwezi conquest Bantu society was based on the clan as a unit but afterwards centralized monarchies appeared - the only place in East Africa where they did so, except for the coast. The centralized monarchy probably evolved when the Chwezi encountered the people already living in the area. The culture and rituals of both peoples merged together but those of the Chwezi were probably dominant. The Chwezi political system had a monarchy, with administrative officials ruling small areas. It also had slave artisans, palace officials and palace women. Their regalia included royal stools, drums, spears, arrows and crowns. It thus appears that the agricultural Bantu peoples of what is now southern Uganda were under the control of a pastoral minority for several generations. The Chwezi rulers are referred to much more in the traditions than their non - Chwezi subjects because the chronicles deal almost entirely with royal and chiefly lineages. Archaeological evidence in western Uganda shows that the Chwezi had royal enclosures (orirembo) which consisted of earthworks. Similar enclosures existed in Karagwe, Ankole and Rwanda almost until the end of the nineteenth century. Examination of the sites of Bigo, Mubende, Kibengo, Ntusi and elsewhere in western Uganda confirms that pastoral people once occupied this region. The biggest ditch system was located at Bigo where it was over ten kilometres long and enclosed good grazing land through which ran a tributary of the Katonga river. The ditch system not only protected large herds of cattle but it was also used for defence. Bigo was most probably the capital. Archaeological evidence and oral tradition indicate that Chwezi culture must have flourished between 1350 and 1500.

The Chwezi empire is usually is usually referred to as Bunyoro-Kitara. It was probably made up of several states joined by family and ritual ties, with a capital centre where the Chwezi kings lived.

Uvinza

-------

Salt has been extracted from the brine springs in the Uvinza area for many centuries. Stratified Iron Age sites covering a long period are very few in East Africa, and the Uvinza pottery succession is important.

Uvinza; an Iron Age salt-working area of western Tanzania, not far from the eastern shore of Lake Tanganyika on a tributary of the Malagarasi which flowed into Lake Tanganyika. Salt, which was widely traded, was evaporated by boiling from the local brine springs after a priest had invoked the tutelary spirits. Anyone could boil salt at Uvinza, provided that he paid a tithe to the local chief. The product was traded throughout the western plateau. The earliest occupation is marked by Early Iron Age pottery akin to Urewe ware, dated to around the middle of the 1st millennium AD. From the lowest layer many lithics were collected, and every layer had a lot of ceramic and burnt material in it. The later Iron Age sequence commenced in the 12th or 13th century and has continued into recent times.

At the Pwaga-Uvinza salt springs Early Iron Age pottery was succeeded as early as the twelfth century by a coarse-fired rouletted ware comparable, though not identical, with the 'Renge' and Bigo wares of the interlacustrine region.

In Kenya and Tanzania the most notable roulette-decorated ceramic type is Lanet Ware, named after its type site in Kenya (Posnansky 1967). This type was first described at the site of Hyrax Hill (Leakey 1931) and has since been documented in Tanzania at Iramba (Odner 1971c) and the Uvinza salt pans near Lake Tanganyika (Sutton and Roberts 1968).

Excavations by the Pwaga brine - spring at Uvinza produced evidence of salt- working from the Early Iron Age down to the 19th century. In the later period clay tanks were constructed for storage or partial evaporation of the brine, before it was boiled in large earthenware pots supported on hearth stones over wood fires. These tanks, as seen, were cut into earlier levels of hearths and wood- ash.

Engaruka

----------

Taken from: Wikipedia; Engaruka.

Not the ruins of an ancient building but the site in which in the middle a simple hut of wood and gras was build. The stones are piled up around to clear the surrounding fields.

Engaruka is an abandoned system of ruins located in northwest Monduli District in central Arusha Region. The site is in geographical range of the Great Rift Valley of northern Tanzania. It is famed for its irrigation and cultivation structures. It is considered one of the most important Iron Age archaeological sites in Tanzania.

The site: Sometime in the 15th century, an Iron Age farming community built a large continuous village area on the footslopes of the Rift Valley escarpment, housing several thousand people. They developed an intricate irrigation and cultivation system, involving a stone-block canal channeling water from the Crater Highlands rift escarpment to stone-lined cultivation terraces. Measures were taken to prevent soil erosion and the fertility of the plots was increased by using the manure of stall fed cattle. For an unknown reason Engaruka was abandoned at latest in the mid-18th century.

Construction of Engaruka has traditionally been credited to the ancestors of the Iraqw, a Cushitic-speaking group of cultivators residing in the Mbulu Highlands of northern Tanzania. The modern Iraqw practice an intensive form of self-contained agriculture that bears a remarkable similarity to the ruins of stone-walled canals, dams and furrows that are found at Engaruka. Iraqw historical traditions likewise relate that their last significant migration to their present area of inhabitation occurred about two or three centuries ago after conflicts with the Barbaig sub-group of the Datoga, herders who are known to have occupied the Crater Highlands above Engaruka prior to the arrival of the Maasai. This population movement is reportedly consistent with the date of the Engaruka site's desertion, which is estimated at somewhere between 1700 and 1750. It also roughly coincides with the start of the diminishment of the Engaruka River's flow as well as those of other streams descending from the Ngorongoro highlands; water sources around which Engaruka's irrigation practices were centered. According to the Maasai, who are the present-day occupants of Engaruka, the Iraqw also already inhabited the site when their own ancestors first entered the region during the 18th century.

Note: in the 16th century the place also traded with the coast as glass beads from this period have been found. Trade objects included ornaments of shell and bone, cowry shells, glass beads, and copper objects.

Engaruka resembles the Sirikwa in displaying very little in the way of social stratification or wealth disparity. Indeed, while its settlement pattern is very different from that of the Sirikwa, the social structure may have been similar, i.e. non-hierarchical, organized around heterarchical principles based on kinship and with crosscutting social institutions and governance by small local councils and occasionally charismatic situational leaders.

The small irrigated fields and channels lined with stones collected to clear the fields.

Tsavo Ethnic Mosaics.

-----------------------

Taken from: The Development and Collapse of Precolonial Ethnic Mosaics in Tsavo, Kenya by Chapurukha M. Kusimba, Sibel B. Kusimba & David K. Wright.

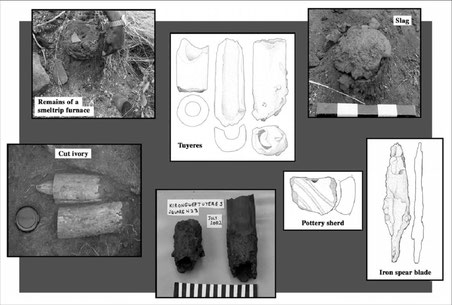

Archaeologists and historians have long believed that little interaction existed between Iron Age cities of the Kenya Coast and their rural hinterlands. Ongoing archaeological and anthropological research in Tsavo, Southeast Kenya, shows that Tsavo has been continuously inhabited at least since the early Holocene. Tsavo peoples made a living by foraging, herding, farming, and producing pottery and iron, and in the Iron Age were linked to global markets via coastal traders. They were at one-point important suppliers of ivory destined for Southwest and South Asia. Our excavations document forager and agropastoralist habitation sites, iron smelting and iron working sites, fortified rockshelters, and mortuary sites.

Over the last 4,000 years, complex cultural mosaics characterized many parts of East Africa. We define mosaics as a group of societies that inhabit a region together and that practice different economies and religions, speaking diverse languages, but related through clientship, alliances, knowledge sharing, and rituals. Conflict, however, was often part of the mosaic as well.

For 1,500 years, Kasigau was the first major stopover inland, being about a three day’s journey from coastal villages and towns. The cairns are the most visible cultural and natural outcrops in the plains and can be seen from one kilometer away. It is probable that they were important cultural markers signifying territoriality, ownership, and sociopolitical status and power. Whatever their meaning, the choice of cemetery (cairn burials) was determined by proximity to coral outcrops. Graves, cemeteries, cairns, and skull internment sites occur widely in the Tsavo region.

When knowledge of iron production was widespread, regions like Tsavo with abundant ores and wood charcoal could sustain major ironworking industrial complexes. One such region is Kasigau, where magnetite ore outcrops abound in the Rukanga and Kirongwe villages. Here our surveys

recovered two large iron-working sites, one at Rukanga and the other at Kirongwe. The sites cover large areas of more than two acres and appear to have been centers of intensive iron production for at least 800 years. Prior to the introduction of domesticated crops, the rockshelters served as seasonal residential areas and ephemeral campsites for hunter-gatherer dwellers. Our surveys revealed that the entire Kasigau hillslope contained a complex maze of terraced fields, as did Ngolia Hills. These terraced fields run across ridges that were sculpted by seasonal springs, streams and small rivers. Each ridge contained extended family houses and their fields.

During the Late Iron Working period 1000 to 1500AD, the regional economic system flourished. A diversity of site types is known from this period in Kasigau, Ngolia Hills and Rhino Valley, Konu Moju and Dakota plains, and other areas. Site occupations dating to this period include rockshelters, caves, villages and homesteads, and pastoral villages and camps. The artifacts and features that are noteworthy at these sites include dry stonework around rockshelter livestock pens, terraced farming, trade goods like ivory and ostrich egg shell, marine shell, and glass beads, and the continued use of stone tools for specialized tasks by many groups, especially the foragers.

Kilimanjaro, Pare and Usambara Mountains.

Ugweno Kingdom (N Pare)

---------------------------------------------

Taken from: A History of Tanzania (Historical Association of Tanazania, 1997, 288 p.) by I. N. Kimambo.

The customers for the luxury products of the Swahili:

In North Pare Mountains a kingdom led by the iron smiths was already existing. The power of the iron-smiths centered on their control of the supply of iron for making tools and agricultural implements on which prosperity depended and for making iron weapons to defend the community. Around these activities revolved the ideas connected with divine ritual functions ensuring continuity and success in society. But at the same time the iron-smiths were obliged to leave most administrative functions in the hands of appointed commoners and clan elders who were not strongly supervised from the center. It is likely that similar developments were taking place in Kilimanjaro and Usambara Mountains.

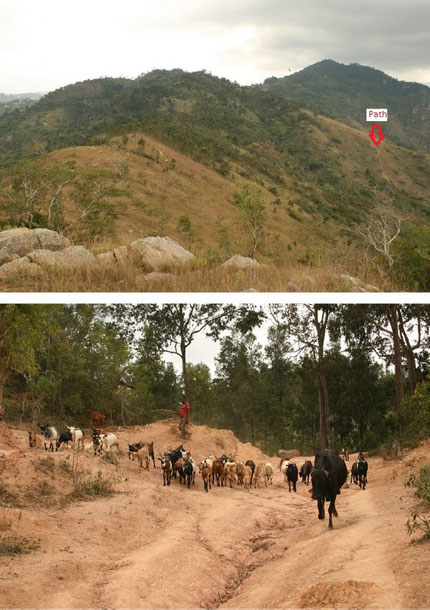

The heavily eroded and deforested Ugweno landscape.

Taken from: Pare people – Ugweno Wikipedia

Shana dynasty (pre 16th c.)

This era can be categorised as the 'age of skill' for the North Pare communities. Although little evidence remains about this era due to 'the great Shana disruption', records show that the Ugweno (or Vughonu) area (=N Pare) was known throughout the region. It was ruled by the Shana clan for centuries and became known as the "Mountains of Mghonu", after an early notably famous Shana ruler, from whom it got its name.

It is the skill of the blacksmiths and the resulting valued iron products that made the area popular that eventually led to the influx of foreign groups.

In addition, there are remnants of a specialized irrigation system that expose hundreds of irrigation intakes and furrows that were constructed during this era. Only when the responsibility for irrigation management shifted from patrilineages to village-level committees (post-independence) were these systems negatively impacted towards near collapse.

After the civil war followed the Suya kingdom (post 16th c.).

The name Ugweno is derived from a notably popular Shana ruler, known as Mghonu, who ruled somewhere between the 13th and 15th century. A precise date is hard to establish given 'the great Shana disruption' when they were deposed of their rule. During his rule, the area was known as the Mountains of Mghonu as far afield as the Taita region in Kenya. These Taita mountains are also the place of origin of the Pare people.

Taken from: A POLITICAL HISTORY of the PARE of TANZANIA ¢ 1500-1900 Isaria N. Kimambo. 1969

Soon after the migration stories, we hear about a famous figure called Mghono or Mghena who is considered by the Washana to have been their first ruler. The Wasuya traditions also agree that Mghono was well known even in Taita, and that the Ugweno Mountains were already known outside the country as the “Mountains of Mghono” from which came the name “Ugweno”. Yet some Wasuya, while agreeing that Mghena was a smith as well as a ruler, try to claim him on their side by saying that he was among the early Wasuya, although the rest of the members of their clan arrived later. The Washana may therefore have been the first rulers who also controlled the iron-working process of the country. Their traditions claim that other people came to live around them mainly because of Washana’s ability to supply the valued iron tools and weapons. The Wasuya had settled a

little farther south in Masumbeni under their leader called Kiringa at the time the Washana centre was a little farther north on a hill called Ngalanga. A northward movement of the Wasuya to the Swia or Suya Hill brought the two groups together. It appears that the Wasuya accepted the authority of the Washana ruler, whose name is unknown, under an agreement which made the Wasuya leader, Angovi, the mnjama or chief minister of the Gweno State about sixteen generations ago. It is difficult to estimate the length of time this state had been in existence before the agreement. Although no details are remembered about the Washana state before their agreement with Angovi, it seems that Ngalanga was the centre of government as well as the iron-working centre. People came there either to get iron articles or to have their cases judged. It therefore happened that the smiths were receiving, not just the payment for their iron products, but also tribute for their political and judicial position. At Ngalanga they had established an initiation ceremony forest (hence the rite was known as mshitu), in which their young men, as well as those of other clans, could attend initiation rites. A visit to this early Washana residence at Ngalanga with the archaeologist, R. C. Soper, showed clear sites of huts which are now under a dense forest of trees and masae (dracaena). After the appointment of Angovi to the position of mnjama, ……he took total power by massacring the Washana ……

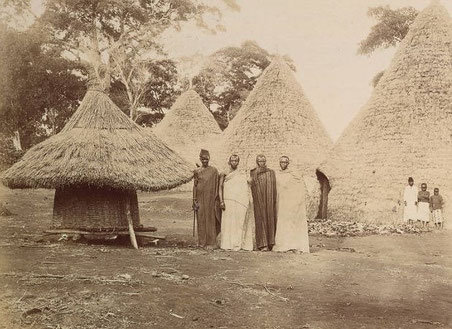

The house of Mangi Meli who fought the Germans.

Taken from: The Civilizations of Africa: A History to 1800 By Christopher Ehret 2002

Among those who settled around Mount Kilimanjaro, a new kind of chiefship, mangi, probably originally meaning “the arranger, planner,’ came into being probably not much before 1000.

The terrain of Kilimanjaro encouraged the founding of a great many small, independent chiefdoms on the eastern and southern sides of the mountain. The newly emerging Chaga communities took up residence on the numerous parallel ridges and valleys that stretched down the slopes, and each ridge became home to one or more chiefdoms.

In a change from the old Mashariki (=Eastern) clan chiefs, the Chaga rulers were not tied to an individual clan but instead ruled over a small territory. The typical mangi would have acted as the adjudicator of disputes and thus would have been able to preside effectively over the melding of different peoples into the expanding Chaga communities of the early second millennium around Kilimanjaro. He (a chief appears nearly always to have been male in this region) had the right to use the age-sets as communal labor in building and maintaining irrigation works, and so he was the “arranger” or “planner” of public works.

Under the authority of the mangi were the njili, the local elders of the several clan groups that made up each chiefdom. The clan headmen retained their leadership over their kin group but were copted along with their people into the new society through their taking up of a new role as members of the chief’s council.