Kuvama (Rio de Cuama now Zambezi)

----------------------------------------------

Ibn Majid (1470) is the only author to mention the place.

Taken from: Wikipedia.

The first European to come across the Zambezi River was Vasco da Gama in January 1498, who anchored at what he called Rio dos Bons Sinais ("River of Good Omens"), now the Quelimane or Qua-Qua, a small river on the northern end of the delta, which at that time was connected by navigable channels to the Zambezi River proper (the connection silted up by the 1830s). In a few of the oldest maps, the entire river is denoted as such. By the 16th century, a new name emerged, the Cuama river (sometimes "Quama" or "Zuama"). Cuama was the local name given by the dwellers of the Swahili coast for an outpost located on one of the southerly islands of the delta (near the Luabo channel). Most old nautical maps denote the Luabo entry as Cuama, the entire delta as the "rivers of Cuama" and the Zambezi River proper as the "Cuama River".

(Note: The Luabo channel is the at the beginning very small branch of the river that starts down from the town of Luabo and forms the provincial boundary with Sofala.)

In 1552, Portuguese chronicler João de Barros noted that the same Cuama river was called Zembere by the inland people of Monomatapa. The Portuguese Dominican friar João dos Santos, visiting Monomatapa in 1597 reported it as Zambeze (Bantu languages frequently shifts between z and r) and inquired into the origins of the name; he was told it was named after a people.

Friar João dos Santos He also described the Zambezi River as a great river which drained into the Indian Ocean through five estuaries, the first estuary being Luabo (Micelo), the second Kwama (Zambezi), the third Old Luabo (Inhamacara), the fourth Linde (Chinde) and the fifth is Quelimane (Cuacua).

According to Dos Santos:

“The island (Luabo) is completely populated by Moors and very kind Caffres almost vassals of the Captain of the Kwama Rivers, who often stay in the island. All merchandise from Mozambique Island in the big embarkations (Pangaios) is unloaded in this island and later, the merchandise is transported in the small boats to the fortress of Sena. Two rivers are navigable during all the year, Luabo (Micelo) and Kwama (Zambezi), while Quelimane (Cuacua) River is navigable only in the winter with much water.”

Duarte Barbosa (1521):

In the mouth of this river (Zuama also Kwama or Cuama), there is a town of the Moors

which has a king and it is called Mongalo. Much gold comes from Benamatapa to this town of the Moors, by this river which makes another branch which falls at Angoya (Angoche). Note: Barbosa makes

a mistake here it is Quelimane on another branch of the river. And the first town of king Mongala might be the Kuvama of Ibn Majid.

Ibn Majid 1470 writes: As recognition point is the high reef, close to Kavama (Kwama): my brother.

And also: Nach measures in Kavama 7 fingers. In front of it (of Kavama) a reef is found, a bit to the East, be afraid to sail in this direction, inquire first.

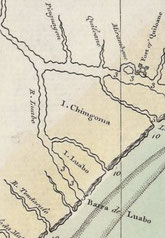

Right: Map showing the Channel and Island of Luabo where the old settlement called Kuvama (Cuama) must have been.

Sena: Hinterland of Kuvama

Taken from: Hilário Madiquida; Archaeological and Historical Reconstructions of the Foraging and Farming Communities of the Lower Zambezi.

Based on written sources, Newitt (1995, p. 12, pp. 53‒54) concludes that by the 1570s Sena had five Muslim families under a leader and ten Portuguese residents.

In the account of the expedition of Fransisco Barreto by Father Monclaro (“Company of Jesus”) in the year of 1569 (in Theal 1964, Vol. 3, p. 223), Sena is described as a small village of straw huts in a thicket. Sena was ruled by a Moor, the son of Mopango, who was a great chief but vassal to Monomotapa. Father Monclaro (in Theal 1964, Vol. 3) also provides information about the death of cattle in this country (probably related to the presence of tse-tse) but that the cattle were brought from the kingdom of Butua.

Father Monclaro likewise describe how the Kalanga ruler the Monomotapa had overruled over these Fumos (locally elected ruler) and that his rule was similar to that of a king, by the obedience he demanded from subjects and through the succession of his oldest son. The Monomotapa was described as very powerful, with large territories and smaller kingdoms that were his vassals (including Butoa and Manica).

Father Monclaro (in Theal 1964, Vol. 3, p. 229): “Generally they are all dressed in pieces of cotton cloth, but are poorly covered. These cloths are made on the other side of the river [Zambesi], and are woven on low looms, very slowly. I saw some at work near Sena. These cloths are called machiras, and are about two varas and a half long and one and a half wide. They gird these machiras round their bodies and cross them over the breast, and the rest of the body is uncovered. They wear horns in their hair by way of finery, which are made of their own locks strangely twisted. These horns are in general use in all Kaffraria, and they shelter the head very well. […] The women wear upon their arms and legs many bracelets of copper drawn very fine, and gold is also drawn very fine, and then made into bracelets.” From this quote it is clear that there was a local production of textiles and also imports such as copper bangles, probably imported from the Zimbabwe plateaux. Father Monclaro (in Theal 1964, Vol. 3, p. 224)

The LFC (Late farming community) ceramics of Sena, date typologically between 11th–12th centuries AD and are similar to that of the site Mavudzu, in southern Malawi (Davison-Hirchmann 1984; Juwayeyi 1993).

Additionally, more than 50% of the Sena pottery includes both surface finishes with burnished red ochre and graphite and incised/punctated decorations. Red and graphite burnished bowls have been reported from coastal assemblages, including Chittick’s (1974) so-called Early Ware at Kilwa, associated with glassbeads. Most researchers have linked these wares to the Comoro Islands, where they constituted a substantial part of the local ceramic assemblages (Fleisher and Wynne-Jones 2011, p. 271).

For stamped ceramics, some elements are very similar to the ceramics of Lumbo tradition, from the coast of Nampula province near Mozambique Island (Sinclair 1987; Duarte 1993; Madiquida 2007). This ceramic tradition is often found in a series of archaeological sites throughout the north coast of Mozambique and dated between the 13th and 14th centuries AD (Sinclair 1985; Adamowicz 1987; Liesegang 1988; Duarte 1993; Duarte and Meneses 1996).

In the excavations in Sena we found different kinds of beads made locally using bones or tusks. All the local beads have white color and no other colors were found. Their shapes are mainly tube, oblate, cylinder and sphere (Wood 2012, p. 69). The value of the beads for the local communities was so high that the beads made from this raw material are likely to be found today in Mozambique in almost all the archaeological sites linked to the long-distance trade network (Sinclair 1985, 1986; Adamowicz 1987; Morais 1988; Duarte 1993; Madiquida 2007; Macamo and Risberg 2007).

As to porcelain imports: all were from after the 15th century from Europe or China. As to glass beads some from India might have been from the medieval period.

Conclusion: Sena on the river Zambezi 190km inland from the delta seems to have been connected to many kingdoms in the interior and sultans on the coast. It does seem to have been without elite that acquired status goods like Chinese or Persian ceramics.