Back to Table of Contents

(5)

To next page

Note on Sumanasantaka (1205) and Krsnayana (13th)

----------------------------------------------------------------------

Taken from: Jiří Jákl (2017): Black Africans on the Maritime Silk Route Jəŋgi in

Old Javanese epigraphical and literary evidence, Indonesia and the Malay World,

Black Africans in Javanese courts: literary reflections.

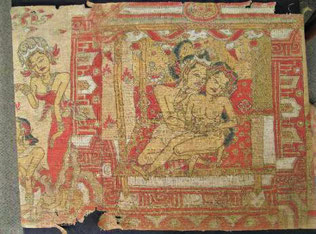

Important evidence pertaining to the social status and position of black Africans at Javanese courts of pre-Islamic period can be gleaned from the Sumanasantaka and Krsnayana, two narrative poems composed in the 13th century in the literary register of Old Javanese (kakavin).

In stanza 141.15 (the second one noted above) black Africans figure as servants of princess Indumati, forming part of her entourage. They are entrusted with carrying her personal belongings at the occasion of her moving house from the court at Vidarbha to the court of her husband, Prince Aja, in Ayodhya.

The black Africans, listed here together with other servile groups of dark-skinned people, are represented in this passage as slaves, the status ascribed to them also in the inscriptional record discussed above. This social status is indicated by the Sanskrit loanword dasa, used in Old Javanese as one of the less ambiguous words to denote enslaved people. In the preceding stanza 141.14 we learn that these sub-status people were part of a wider category of unfree people, denoted by the native term hulun, referring in Old Javanese to slaves as well as bondsmen (Zoetmulder 1982: 649). The Sanskrit loanword dasa, uncommon in Old Javanese literary sources, may have denoted in particular slave outlanders, enslaved men and women shipped to Java from other parts of Indonesia as well as from more distant lands. Interestingly, the passage indicates that black Africans serving at Javanese pre-Islamic courts, similar to other servile groups, were organised in units (jəŋgi sajuru), led by a ‘chief’ ( juru). In Old Javanese juru denotes a head of an administrative or military unit, as well as of a professional group of producers, servants, and merchants.

The term kaliliran, meaning in Old Javanese ‘inheritance, heirloom’ (Zoetmulder 1982: 777), and used here to refer to African slaves, actually suggests that dark-skinned slaves represented a category of servile people passed on to Indumati, plausibly by her parents. In parallel with Old Javanese inscriptional record, black Africans are listed in the stanza quoted above along two other classes of dark-skinned people, the bondan and pujut (Negritoes)

The first passage in the Sumanasantaka that gives us an insight into the social position of black Africans depicts a festive procession of Prince Aja and Princess Indumati approaching a paprasan pavilion to undergo a pras ritual as part of their wedding ceremony:

Here Princess Indumati stands for the moon. (indu: ‘the moon’)

The black African maiden, entrusted with carrying one of the two ceremonial parasols, is undoubtedly a member of the servile ‘unit of Africans’ discussed in some detail earlier. The text identifies this African slave as rara, a young girl, giving us an interesting piece of information that very young girls, probably born in Java, were part of the local African community.

The passages confirms a presence of black Africans in the environment of the inner court servants, and strengths our view that restricted numbers of them may have been socially less marginal than scholars commonly assume. Creese (2004: 54–55) was the first who noted the importance of this passage for the cultural history of Java, observing: ‘The bearer of the betel box was usually the most favoured royal retainer in the immediate household of a prince or princess. Apparently even those who came from distant parts of the world could rise to this most privileged of positions at court.’